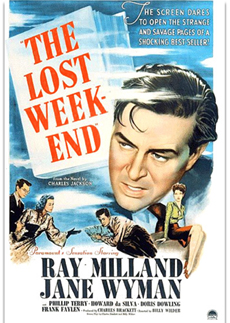

I was excited to see The Lost Weekend because the title of the

movie has become such a pop- cultural reference. Of course, I was also

interested because it was helmed by acclaimed director Billy Wilder,

who gave us such classics as Double Indemnity, Sunset Blvd., Sabrina,

The Seven Year Itch and Some Like It Hot.

In addition, I was curious to finally see a performance by Jane Wyman,

the first wife of Ronald Reagan, mother of conservative radio talk show

host Michael Reagon. She died a year ago in September.

The movie starts with Don Birnam (Ray Milland), a down-and-out writer,

and his brother, Wick Birnam (Phillip Terry), about to take a trip into

the country, where Wick promises a weekend full of fresh milk and cider,

with the implication being not a drop of alcohol. At this point, Don

claims that he's been alcohol-free for 10 days, but the viewer is tipped

off to his lie by a bottle of alcohol, tied to a rope outside his bedroom

window.

Faced with the prospect of a dry weekend, Don seeks to delay it, suggesting

that they take a later train while Wick accompanies Don's girlfriend,

Helen St. James (Jane Wyman), to a play. Don says that way she won't

have to go alone and he can finish his packing. This would have been

a different movie if Wick had insisted on making the earlier train,

but he relents, therefore giving Don the opportunity to slip out of

his grasp. The weekend of shame begins by Don stealing $10 meant for

the maid in order to go to a liquor store and buy two bottles of rye,

which he intends to stow away for the trip, then parking himself on

a barstool, where he intends to drink until it's time to leave for his

train.

Of course, anyone who's dealt with somebody who's really drunk can

predict the outcome. The bartender is unable to shake Don from his stool

in time to make the train. Thus, his downward spiral truly begins as

his brother storms off for his long weekend without him, leaving Don

to four days of uninterrupted indulgence.

Through it all, Don's longsuffering girlfriend, Helen, strives to contact

him, to rescue him from himself. Through flashbacks to the beginning

of their relationship, we learn that, while she was initially ignorant

of his condition, ever since finding out about it, she has always been

supportive, convinced that she could bring him out of it.

Jane Wyman manages to combine both sweetness and strength, so that,

far from appearing to be a naive enabler, she seems like a woman who's

clearly aware of her boyfriend's problems and yet refuses to give up

on the man she loves.

The problem is, as the movie shows, that you can't force somebody else

to face up to their addiction. It has to come from them, and this realization

typically comes from exactly the sort of experience that happens in

this movie: where somebody sinks to newer and newer lows, hits bottom,

and is scared into a realization of what they're doing to themselves

and their friends and family.

Wick makes a remarkably insightful speech in the early part of the

film, as he's leaving for the country without his brother. To paraphrase,

he tells Helen that, no matter how many times they pick Don up, brush

him off and set him on his feet again, he continues to screw up. Maybe

it's time, Wick says, to stop helping him. While this might seem cruel,

that sort of tough love may be the only way someone can realize the

depth of their problems.

Certainly, therefore, the filmmakers understood something about addiction.

Helen even acknowledges that it's a disease, saying she can't turn her

back on Don any more than she could if he had a heart condition. Don

delves into the thinking of an alcholic, relating the story of how he

kicked alcohol for several weeks when he was first dating Helen, but

when it came time to meet her parents, he needed just one drink for

courage. Of course, he relates dejectedly, it never stops with just

one drink.

Viewers of this movie might wonder whether Don will truly reform after

this weekend. It's hard to say, especially when we're given the indication

that he has suffered terrible things before and resolved to change.

The one difference about this lost weekend, however, may be that he

truly realized how lost he was, without his brother to keep him from

reaching the worst depths of the addiction. Perhaps, then, there is

a possibility that he may change.

As far as the filmmaking itself, it's shot in a very gritty, film noir

style. Stark shadows play a role in various places, as well as the contrast

between light and dark. The movie starts out with a flat brightness,

which makes it seem almost like a comedy, but as Don descends further

and further into self-destruction, the movie gets darker, shadows get

longer, and Don himself becomes more disheveled.

The script is based on a novel by Charles R. Jackson, and it tends

towards melodrama in parts. This is rescued somewhat by the fact that

these characters actually seem to believe what they are saying, especially

Milland, who in a touching scene, reveals to a bartender his struggles

as a writer. As he complains that the words escape him, he nonetheless

launches into a moving depiction of what it's like to be an alcoholic

and to awake in the harsh light of morning with no prospect of booze

until the stores open.

To prepare for the role, Milland spent a night in Bellevue Hospital

(where part of the film was shot), and he also stopped eating as much,

since many alcoholics forget to eat, as well.

The movie attracted a lot of controversy before it was released, with

both alcohol companies and temperance groups besieging the studio. This

was one of the first times that alcoholism was portrayed so starkly,

instead of used as a punchline. Yet, once this "dangerous movie"

was released, reviewers peppered it with praise, and it went on to box-office

success, a Best Picture win and a Best Actor win for Milland.

The one truly distracting element is the heavy-handed use of the soundtrack,

which uses suspense music, featuring the first on-screen use of the

theremin, which would become a staple of 1950s science-fiction movies.

The music is used to compound the feelinsg of disorientation and despair,

but it's so overwhelming it reaches the point of absurdity. Perhaps

a viewer in 1945 would have found it less distracting, since soundtracks

were more prevalent in those days. But to a modern viewer, it clashes.

I'd love to watch some of the key scenes without it and see what sort

of impact they have, such as the scene where Don tears apart his apartment,

looking for a bottle he had hidden while drunk.

Overall, The Lost Weekend holds up remarkably well as an unflinching

look at the reality of alcoholism.

Rating (out of 5): ****

Musings

on Best Picture Winners